Medicaid Work-Reporting Requirements in Florida Still Do Not Make Sense

This legislative session, Florida representatives have proposed SB 1758/HB 1453, which impose work-reporting requirements (WWRs) for adults aged 19–64 (SB 1758) or 18–64 (HB 1453), who don’t meet certain exemptions. These Medicaid beneficiaries would be required to report 80 hours of work per month including paid employment, or other activities such as job training or school. In the past, FPI has highlighted that WRRs in Florida do not make sense. This is now magnified with the recent passage of H.R. 1, titled the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA). OBBBA only authorizes WRRs for Medicaid expansion populations. Florida has not expanded its Medicaid program, so WRRs are not permissible. Further, implementing WRR’s in Florida is fiscally irresponsible, given the very small number of Medicaid beneficiaries who would be affected, and the steep administrative costs necessary for implementation. Finally, adults subject to these requirements would be required to work themselves into the coverage gap, causing thousands more Floridians to become uninsured.

For years, Medicaid WRRs have been debated in Florida and rejected. In 2018, bi-partisan leadership expressed their reservations about implementing these requirements. “We don’t have childless able-bodied working age adults in our system, so I don’t know how that would transpose to us.” This continues to be the case today.

Questionable Legality — Florida’s Proposals Conflict with the One Big Beautiful Bill Act

In July 2025, the U.S Congress passed H.R.1, titled the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act.” It mandates that all states that have taken up Medicaid expansion impose WRRs as a condition of Medicaid eligibility. This means that the beneficiaries enrolled under a state' s Medicaid expansion category must complete at least 80 hours of “community engagement activities” per month through some combination of work, community service, education or participation in a work program. The law provides exemptions for certain categories of people, such as Native Americans, parents and caregivers of children 13 years or younger or disabled individuals, medically frail individuals, and more. Notably, the Florida proposals also include a number of these exemptions, but they are irrelevant in our state.

That’s because Florida has not expanded its Medicaid program. Florida’s program only includes coverage for mandatory traditional non-expansion populations, such as very low-income parents.

H.R.1 is clear — WRRs only apply to states that have expanded their Medicaid programs. Further, OBBBA unequivocally states that the WRRs provisions cannot be waived (42 U.S.C. sec. 1396a(xx)(10)). This means that non-expansion states like Florida are prohibited from obtaining a waiver to impose WRRs on Florida’s non-expansion Medicaid population.[1] N[EL1] [EL2] otably, Congress could have elected to authorize WRRs for traditional mandatory Medicaid populations or allow waivers of the work requirements. Instead, it chose to do the exact opposite, explicitly prohibiting such authority. Florida’s proposals disregard these fundamental OBBBA restrictions.

The Affected Population Is Too Small to Justify the Steep Administrative Costs for Implementation of WRRs

In Florida, only 11 percent of the Medicaid non-disabled population are adults ages 19–64, none of which are childless. Of that small number of parents and caretaker relatives, 68 percent already work. A bill analysis of SB 1758 stated that there were 117,789 people who would be subject to this work-reporting requirement. As of December 2025, there were 3,911,857 individuals enrolled in Florida’s Medicaid program. This means that, if enacted, this bill would seek to impose costly standards on just 3 percent of people in the program, mostly consisting of people who already work.

Georgia was one of a few states that implemented work-reporting requirements for Medicaid on their small expansion population, and the state lost money mostly due to the new administrative costs. Georgia’s Pathways program has cost the state tens of millions of dollars, while only covering a small number of people. In fact, an analysis of the first year of Pathways showed that the state spent five times more per person for the program compared to what it would have spent if it had just expanded Medicaid ($2,490 vs $496). Another analysis found that after two years, Pathways cost Georgia $110 million, and two-thirds of that amount was spent on administration and operation costs.

Florida’s Medicaid eligibility and enrollment infrastructure is already stretched thin and unable to meet current needs. This was highlighted in a Florida federal district decision, made in January 2026. The decision found that the state’s notices terminating Medicaid eligibility “border on the incomprehensible,” are “confusing, vague and misleading,” and violated the due process of tens of thousands of Floridians. These problems were shown to be exacerbated by under-resourced call centers, with restrictive hours, long wait times, and untrained staff. The state’s priority should be an investment towards correcting these systemic deficiencies before taking on new administrative costs. Significantly, OBBBA mandates that states take on even more administrative costs through implementation of new verification processes, notice, and outreach requirements. None of these costs are factored into state and legislative fiscal analyses of these WRRs proposals.

In summary, this legislation would be expensive to enact — and for a very small return, if any.

Working Your Way Out of Health Care Coverage

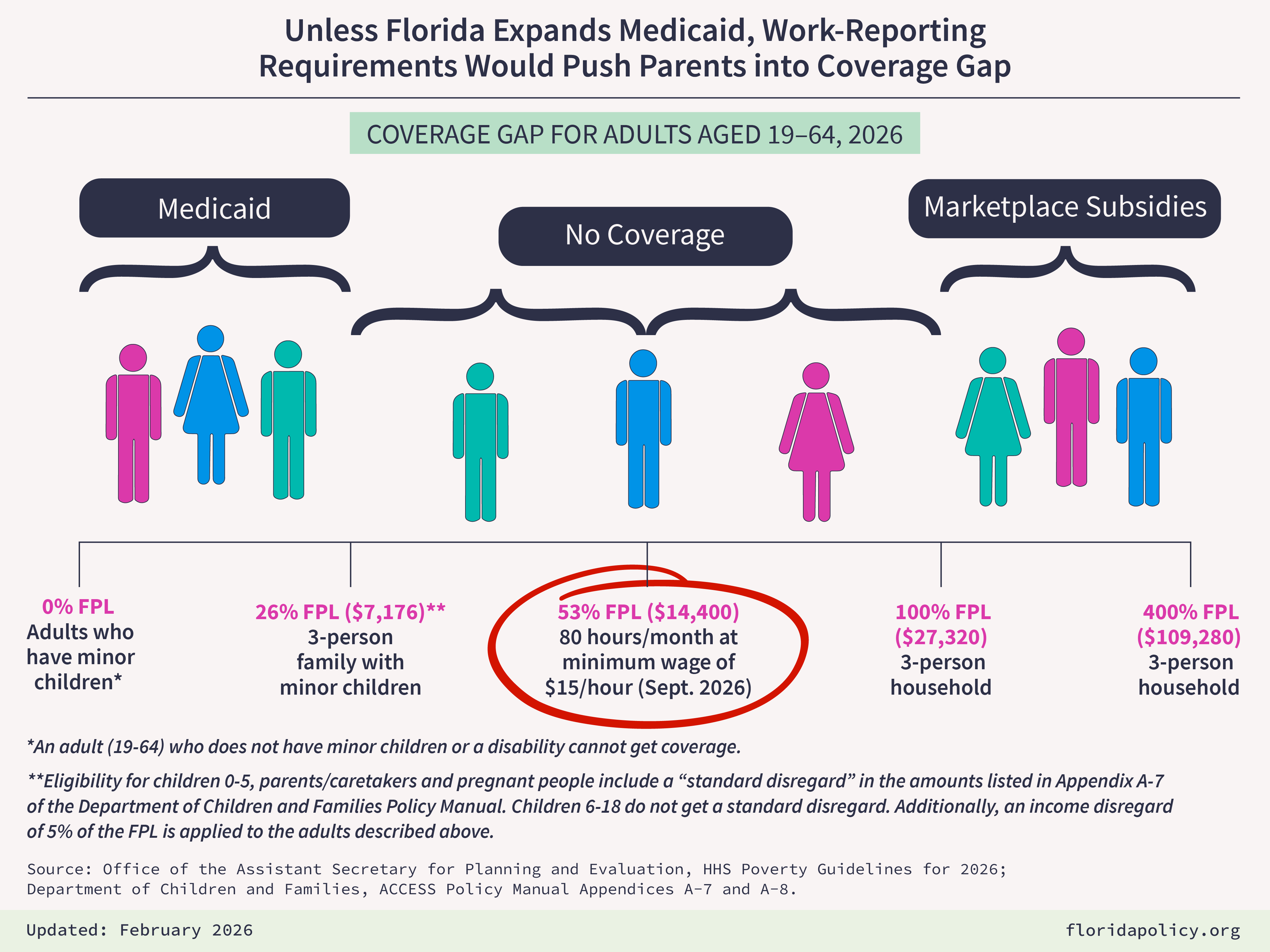

The proposed WRRs will lead to thousands of Floridians becoming uninsured due to a catch-22. To qualify for Medicaid in Florida, families must make only up to 26 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), which is $7,176 for a family of three. In contrast, Medicaid expansion covers adults up to 138 percent of the FPL — which is $37,701 for a family of three. Florida has intentionally set its Medicaid eligibility level below the minimum wage for 80 hours of work per month. With Florida’s minimum wage moving to 15 dollars per hour, working 80 hours per month would increase the family's income to $14,000 annually — disqualifying them from Medicaid coverage, and leaving them too poor to access Marketplace Insurance, which requires an annual income of $27,320. This would only add to Florida’s uninsured rate, which is among the highest in the nation.

Proponents of this bill argue that this is a good opportunity for families to achieve self-sufficiency, but making health care coverage more difficult to attain and keep through a work-reporting requirement does not help families break through deep-seated financial barriers. More paperwork given to families who are already burdened does not eliminate barriers to self-sufficiency but instead has been proven to cause more undue harm and stress. This attempt to “incentivize” individuals who are already working is misguided and should be reconsidered, as work reporting requirements in Florida do not make sense.

______________________________________________________

Addendum

[1]Analysis of Florida SB 1758 and Fiscal Note

Florida SB 1758 proposes to impose work requirements that would violate the statutory requirements of the One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB), enacted as P.L. 119-21. The OBBB at §71119 creates a new provision in Medicaid law, §1902(xx) of the Social Security Act, generally requiring work requirements for expansion populations. Citations below refer to that new provision at §1902(xx). Specifically, SB 1758 would violate two very basic requirements established by OBBB in §1902(xx).

First, the OBBB at §1902(xx)(3)(A)(i)(cc) effectively bars work requirements for individuals in traditional mandatory Medicaid categories (described at §§1902(a)(10)(A)(i)(I) through (VII)), including the very low-income parents group (also known as “Section 1931 Parents”). Under the terms of OBBB, Florida cannot impose work requirements on any of those traditional populations. The work requirement in OBBB was explicitly targeted at expansion populations. (Note that the traditional mandatory individuals covered under §1902(a)(10)(A)(i)(IX) also cannot be subject to work requirements, though the OBBB exempts them through a separate mechanism, a “Specified Exclusion” under §1902(xx)(9)(A)(ii)(I). In short, the only traditional mandatory group that can be legally subject to the work requirements are §1902(a)(10)(A)(i)(VIII) Medicaid expansion adults.

Second, the OBBB at §1902(xx)(10) prohibits waivers of the OBBB work requirements, including the eligibility rules stated in the prior paragraph. This provision of OBBB was effective upon enactment (July 2025) and explicitly prohibits waivers of the terms of the work requirement. CMS recently confirmed this in guidance issued on December 8, 2025, writing that “[t]he provisions of section 1902(xx) of the Act cannot be waived under section 1115 demonstration authority.” Under OBBB, a state is thus barred from receiving such a waiver to impose work requirements on traditional mandatory populations who are not in Medicaid expansion. For example, a state could not get a waiver to impose work requirements on traditional mandatory parents.

In summary: OBBB does not allow Florida to impose work requirements on mandatory traditional non-expansion populations, such as low-income parents, nor does it allow waivers to do that. Congress could have elected to authorize work requirements for traditional populations or allow waivers of the work requirements, but instead it chose to do the exact opposite, specifically and explicitly prohibit such authority.

Some of the confusion underlying SB 1758 may be explained by a legal error in the Florida Senate “Bill Analysis and Fiscal Impact Statement.” That document is likely relying on OBBB language at §1902(xx)(1) to conclude (on page 4) that Florida “may do [work requirements] under a section 1115 waiver or state plan amendment.” While this is true in general terms, §1902(xx)(1) also stipulates that this is “subject to the succeeding provisions of this subsection.” In other words, such 1115 waivers or SPAs of course are still subject to all the subsequent requirements of the OBBB, including the limitations at §§1902(xx)(3) and (10) described earlier. Thus, this is not a freestanding authority to do work requirements that is untethered from the OBBB terms for work requirements. The purpose of the reference to section 1115 in §1902(xx)(1) is to allow states to do work requirements as part of 1115 expansion demonstrations, not to allow waivers of the terms of the work requirements themselves. For example, if Florida chose to do a Medicaid expansion through section 1115, under the OBBB statute the State could impose the work requirement on that population, but it could not waive the terms of the requirements themselves (as confirmed in CMS guidance referenced earlier).