Note: In the 2024 release of this report, FPI analyzed The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data to explore the prevalence of heat-related illness and deaths in the state (based on emergency room visits and hospitalizations). FPI was unable to update this data because of federal funding cuts that included the CDC’s environmental health tracking dashboard. FPI’s 2024 report also included U.S. Census Bureau data on social vulnerability to heat, but this is an experimental data set and has not been updated since 2022.

Executive Summary

While sunshine and warm weather draw Florida visitors and residents alike, excessive heat is a looming threat to over half a million Floridians who work outdoors.[1] These Floridians work in myriad roles, such as landscapers, amusement park attendants, construction workers, and agricultural workers, among others.[2] Given a lack of state and federal mandates plus a 2024 law blocking cities and counties from implementing their own laws, the choice to protect working Floridians from heat-related illness is ultimately up to employers. Furthermore, unions face increasing challenges in negotiating better conditions for working Floridians.[3] As such, Florida’s workers have little reprieve from the extreme heat.

Following up on its 2024 report, “High Heat, Higher Responsibility: The Sunshine State Must Enact Policies to Protect Working Floridians,” Florida Policy Institute (FPI) analyzed National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data and found:

- Florida experienced abnormally high temperatures during every month of 2024.

- An estimated 611,100 Floridians work outdoor jobs.

- Florida's top three outdoor industries are construction, amusement and recreation, and landscaping.

Statewide intervention remains paramount. To protect working Floridians and keep businesses operating smoothly, Florida must spread awareness about heat-related illness, repeal the preemption of local heat exposure ordinances, and pass a statewide law that covers all outdoor workers.

Heat-Related Illness is a Growing Concern in Florida

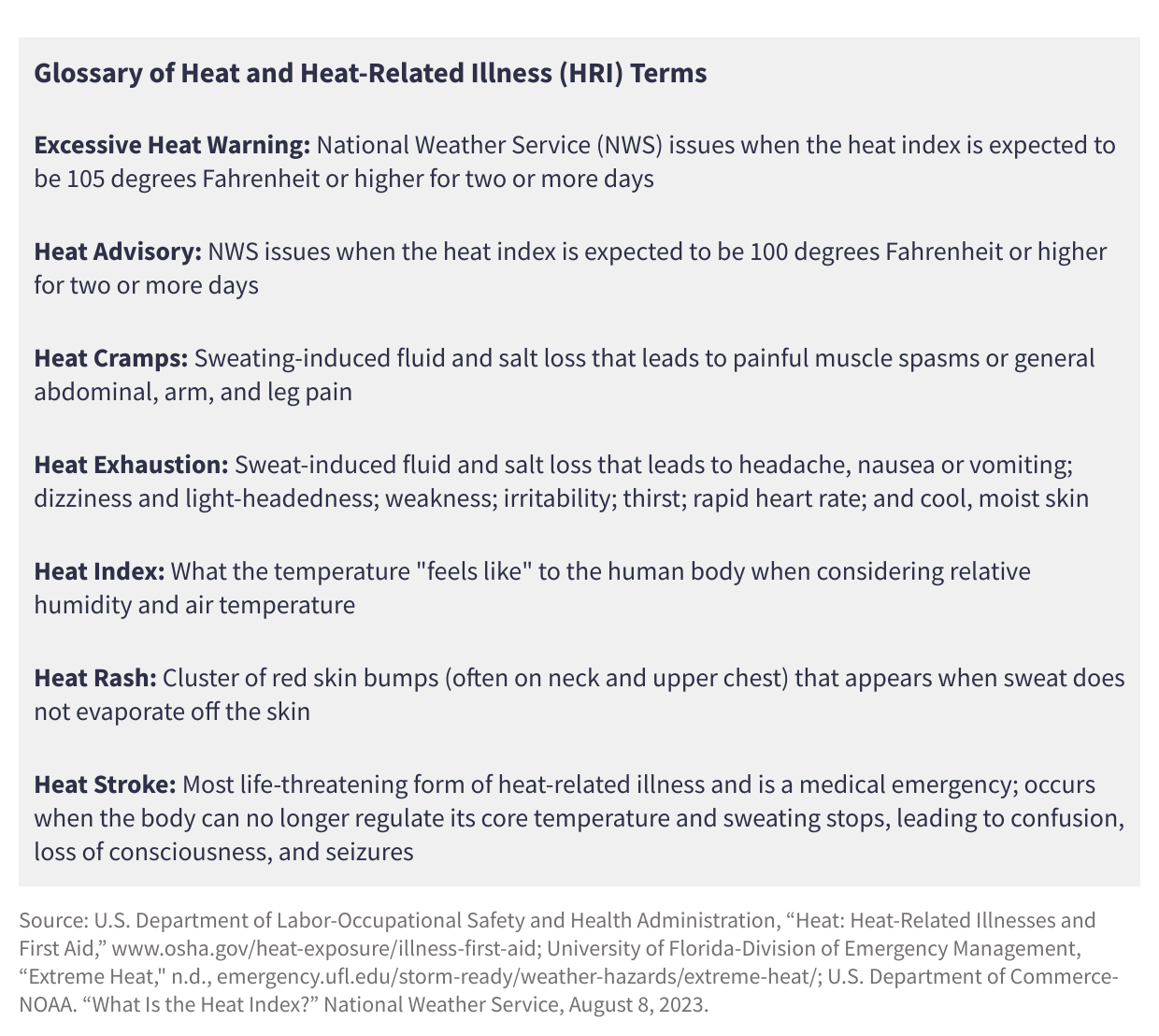

Heat-related illness (HRI) is an umbrella term for people's different responses when their bodies cannot regulate internal temperature and cool down.[4] These responses range from heat rash to heat exhaustion to heat stroke, which can be fatal. (See Glossary for complete definitions.)

There is strong scientific consensus that, since the Industrial Revolution, there has been a significant rise in heat-trapping gases (“greenhouse gases”) in Earth’s atmosphere, causing warmer temperatures and other abnormal weather events.[5] While individual consumption contributes to climate change nominally, research shows that approximately 80 corporations — mainly oil companies — are responsible for over 70 percent of the world’s fossil fuel and related emissions. These emissions are the most significant drivers of greenhouse gases and, subsequently, climate change.[6]

Meanwhile, in 2024, Earth experienced its hottest days in recorded history.[7] In the United States, 2024 was the hottest year since 1850; in Florida, 2024 had the hottest summer since 1895.[8] Worse, in every month in 2024, the state experienced above-average temperatures. (See Figure 1.)

Moreover, Fort Lauderdale, Fort Myers, Orlando, Palm Beach, and Punta Gorda saw their hottest heat seasons (May to October) ever.[9] For context, even a one-degree increase in temperature can have widespread impacts. In Florida, a one-degree increase can impact crops, predispose the state to more frequent storms and extreme heat, and further sea level rise and coastal erosion.[10] Furthermore, when the heat index exceeds 90 degrees Fahrenheit, the chances of heat cramps, exhaustion, and stroke increase.[11]

Over Half a Million Working Floridians Are Vulnerable to Heat-Related Illness

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 611,100 Floridians work outdoor-dominant jobs.[12] Other research puts this number as high as 2 million.[13] Among these, construction, landscaping, and amusement and recreation are the top outdoor industries in the state (See Figure 2). Therefore, HRI is of particular concern for these working Floridians.

Labor inequality research shows that overall, Latino and Black people die at work at much higher rates than other people.[14] Considering gender, men are three times more likely to suffer from heat-related incidents at work than women. Overall, men tend to work in more dangerous occupations, compounding their risk for injury. People under 30 are also twice as likely to experience HRI than older working people. Other risk factors for HRI include prior health conditions, lack of regular medical care access, and immigration status. Regardless of the person, those without access to air-conditioned resting or living spaces are also more likely to suffer HRI on the job.[15] Especially for those working in lower-wage positions, dealing with heat-related illness can wreak havoc on people’s finances, health, and job security.[16]

HRI also hurts businesses and the economy by reducing labor productivity. For example, at 77 degrees Fahrenheit with 30 percent humidity, the average person can work at 95 percent capacity; at 95 degrees Fahrenheit with 50 percent humidity, work capacity drops to 68 percent.[17] In Florida, two of the top three outdoor jobs are key drivers of its economy — construction, along with amusement and recreation (See Figure 2). Because of HRI, Florida loses an estimated $11 billion annually in productivity.[18]

Finally, compelling data suggests that people with minimum- and other low-wage jobs are particularly prone to HRI. The Institute of Labor Economics finds that working people in the bottom 20 percent of wages suffer five times as many heat-related injuries as those in the highest 20 percent. This is partly because those working in lower-wage jobs may lack other promising job prospects, giving them less negotiating power to demand safety measures from their employers.[19]

Furthermore, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is limited in countering HRIs, though its investigations have increased significantly since 2022.[20] OSHA has a Heat-Related Illness Campaign advising employers on what to do, and it can fine them in egregious cases where injuries and death occur. Still, neither Florida nor federal law mandates specific heat exposure standards nor do they require employers to train or educate workers on the signs of HRI.[21] While OSHA is working toward an enforceable HRI standard, it is a multi-step process, and as of this report, still must be finalized with public input.[22]

The risks are compounded for those who are not acclimatized, or accustomed to, working in the heat. OSHA underscores that unacclimatized workers are at risk for heat-related illness even at temperatures as low as 77 degrees Fahrenheit.[23] At higher temperatures, these HRIs can become deadly. In April 2022, for instance, the heat index reached 89 degrees, and a 35-year-old farmworker lost his life on his second day on the job. OSHA fined the Wauchula Florida farm contractor $29,000 for failing to implement a heat illness prevention plan for new hires.[24] That December, OSHA fined an Okeechobee labor contractor $15,625 for the death of a 28-year-old Mexican immigrant who suffered from an apparent heat stroke on his first day in agriculture work, when the heat index reached 90 degrees. The employer failed to take preemptive measures and ignored the young Floridian’s complaints of cramps and fatigue, which are clear signs of heat exhaustion.[25]

As a best practice, outdoor workers are often advised to limit sun exposure with personal protective equipment (PPE) like hats, light-colored articles of clothing, and long sleeves. Unfortunately, some of this clothing can still trap heat and contribute to HRI, depending on the material.[26] Working people may also reject certain PPE because of cultural norms and affordability (when their employer does not provide it).[27]

Admittedly, many outdoor workers eventually become accustomed to laboring under higher temperatures and direct sun exposure. Still, even the most acclimatized workers are not immune to HRI during heat waves, especially people returning from time off or those who are less physically fit.[28] Plus, Florida has been issuing heat advisories earlier and more frequently, so even acclimatized workers face increasing risks.

While all of Florida’s outdoor workers are at risk of heat-related illness, a handful of industries stand out, such as construction, amusement and recreation, landscaping, and agricultural (or farm) work. All industries except for farmwork employ the most Floridians in the state, so these are crucial roles to emphasize given the sheer number of people who occupy them. (See Figure 2.) While their numbers may be smaller (less than 10,000 employees), farmworkers’ contributions are hugely impactful to the state’s agricultural industry.

Farmworkers remain especially vulnerable to heat-related illness, as the immigrants and independent contractors who do much of this outdoor work lack full workplace rights.[29]

Construction

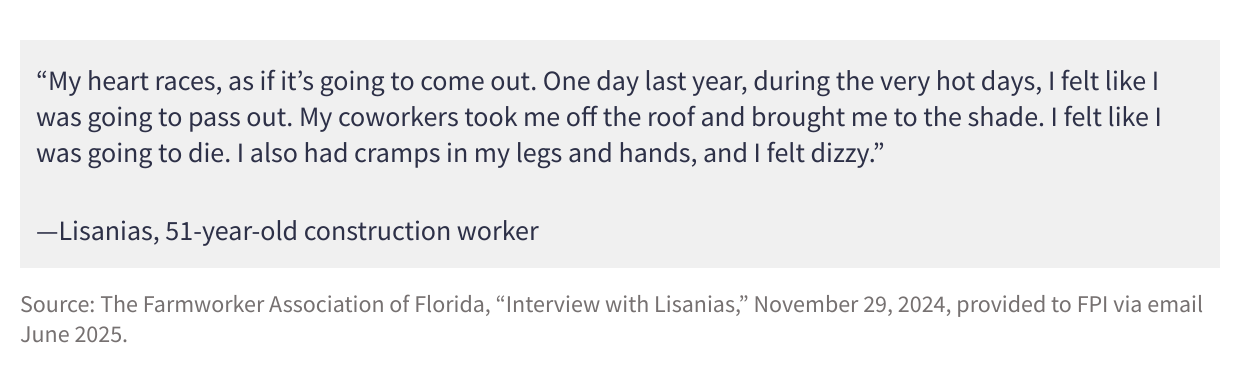

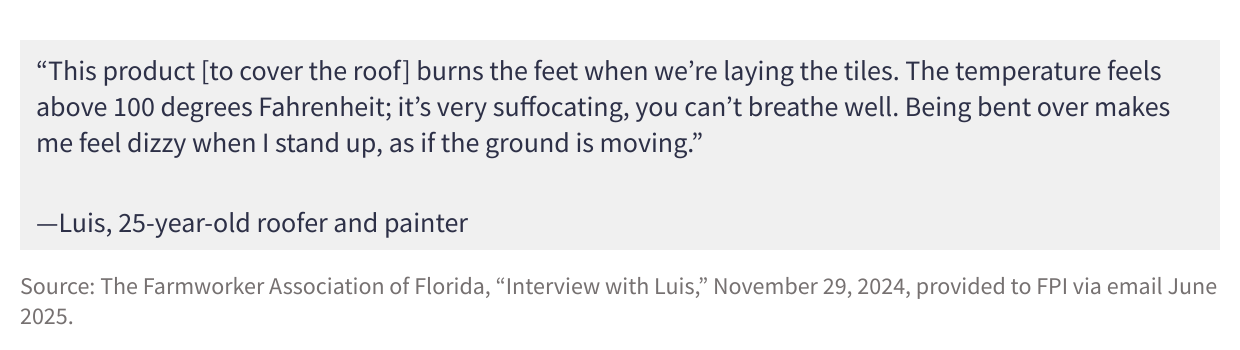

The top outdoor occupation in Florida is construction, employing an estimated 262,530 Floridians as day laborers, first-line supervisors, roofers, masons, equipment operators, and more.[30] Those working in construction perform a variety of roles, including on large-scale engineering projects (e.g., highways), and new and existing residential and commercial buildings.[31] The construction industry is physically demanding, no matter where people work. Still, in Florida, prolonged hours under direct sunlight and high humidity make the work all the more dangerous. Research shows that heat exposure limits the ability to think and make decisions properly, a major hazard in work environments characterized by “heavy machinery, moving vehicles and objects, or working on elevated surfaces.”[32]

Nationally, small construction firms (i.e., with revenue under $1 million) represent at least 79 percent of the heat-related cases that OSHA investigates. In general, smaller firms cite less resources, staff, and knowledge to mitigate against high heat. Some are also under the false impression that addressing the issue is not frequent enough to justify the cost to prevent it.[33] In Florida, the most recent U.S. Census data shows 62,231 construction businesses — 44,548 of which (71.6 percent) have less than $1 million in annual sales.[34] Thus, most of Florida’s construction workers are at small companies and are more likely to experience heat-related illness.

Landscapers and Groundskeepers

The second-highest outdoor occupation in Florida is landscaping and groundskeeping, employing an estimated 84,250 people. (See Figure 2.) These Floridians perform physically demanding work, like mowing lawns, trimming hedges, and installing and maintaining land on residential and commercial properties.[35] Excessive heat and high physical exertion make landscapers and groundskeepers particularly vulnerable to heat-related illness.

For example, in 2024, the federal government fined a landscaping company in Sarasota County $16,102 for the heat-related death of an employee caused by the company’s failure to ensure workplace safety.[36] Recently, OSHA made this industry one of its target groups for outreach on heat-related illness.[37]

Agricultural Workers

People working in agriculture tend to popular crops like oranges and strawberries, operate farm machinery, and care for livestock, among other duties.[38] Agriculture is also one of the most dangerous professions in the country.[39] Particularly, farmworkers often have little power to mitigate safety concerns, as they tend to be independent contractors, seasonal workers with few legal rights, or undocumented immigrants with even fewer rights.[40] Moreover, farmworkers are discouraged from taking breaks because they operate on a piece-rate wage system, where their payment is contingent on how much they harvest.[41]

When most of the country’s labor laws were first enacted, farmworkers were explicitly left out to appease wealthy Southern landowners.[42] Since then, advocates have made significant strides in securing protections for farmworkers. However, there are still numerous ways in which they are excluded from labor laws — including the right to join a union and in some instances, safety regulations under OSHA.[43] However, in egregious cases of death, the federal government has stepped in; although, as aforementioned, it usually only has the authority to do so after the fact. For example, in 2024, an OSHA investigation led the U.S. Department of Labor to fine a Belle Glade farm contractor $27,655 for failing to prevent the heat-related death of a 26-year-old Mexican immigrant employee.[44]

Many farmworkers are seasonal, especially in Florida, which makes them less likely to acclimate to new jobs. Additionally, most are immigrants, so they may face language barriers or have a precarious documentation status, which makes advocating for reprieve from harsh conditions more difficult.[45]

For these reasons, reliable farm and agricultural employment estimates remain elusive. Still, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that at least 10,550 farmworkers are employed outdoors in Florida (see Figure 2 and Methodology). However, the Florida Department of Health puts this number as high as 200,000 when considering seasonal workers and independent contractors.[46]

Amusement and Recreation

Florida would not be the state it is today without tourism and recreation, including the international appeal of its famous amusement parks. While many more work in the broader hospitality industry, an estimated 48,000 amusement and recreation attendants (see Figure 2) are outdoors most of the day — attending to rides, working concessions, or maintaining equipment for sporting events, among other duties.[47]

Although these working Floridians are exposed to dangerous heat, addressing heat-related illness is ultimately up to the companies for which they work. One of the largest employers of amusement and recreation workers in Florida is Walt Disney World,[48] and unionized workers have succeeded in getting the company to agree to water, sunscreen, and modified performances in cases of extreme heat.[49] Still, two actors passed out on the job last summer, citing employer delays in repairing a faulty air conditioner.[50]

Yet, in the 2024 legislative session, Florida lawmakers, with support from a large-business group, passed a measure that now blocks local governments from requiring private employers to implement protections against heat-related illness.[51]

Florida Can Mitigate Heat-Related Illness with Smart Policy Changes

Although extreme heat is becoming commonplace in the Sunshine State, heat-related illness should not be when there are commonsense solutions to prevent it. For years, farmworkers have advocated that all employers heed these concerns statewide, to little avail.[52] The Florida Legislature recognized the dangers when it unanimously passed the Zachary Martin Act to protect student athletes from heat-related illness in 2020.[53] Now, all Floridians who work outdoors deserve the same.

There are three broad ways for state legislators to ensure Florida’s outdoor workers are protected from HRI:

1. Educate employers and working Floridians on the dangers of working in the heat.

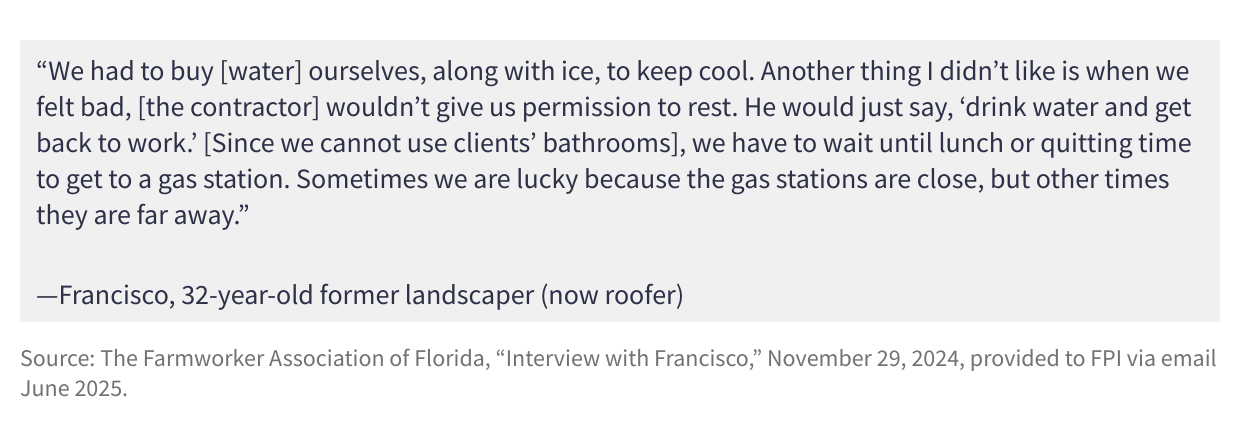

There are numerous ways to mitigate heat-related illness; however, central to every approach are three concepts: water, shade, and rest.[54] Florida’s farmworkers also echo the need for water and shade in particular.[55] The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health implores businesses to train all staff to monitor hot weather advisories, administer first aid, learn the overall signs of HRI, and understand how to gradually acclimatize employees to hot and demanding environments.[56]

State agencies must proactively spread awareness on the dangers of, and solutions to, working in high heat. Instead, this task unfairly falls on immigrant-driven grassroots groups and unions to negotiate.[57]

2. Stop state preemption.

The Florida Legislature has a history of preempting (or blocking) local governments from passing inclusive worker protections.[58] In 2024, this manifested in HB 433, which blocks local governments from passing ordinances that require companies to mitigate heat exposure for their employees.[59]

Without a statewide law to protect all Floridians who work outdoors, legislators should not prevent cities and states — some of which may experience hotter days than others — from passing policies that serve their residents best. The Legislature should repeal HB 433 and reject further attempts to preempt local governments.

3. Pass and enforce statewide heat illness prevention standards.

The federal government has many informational campaigns and resources for workers and employers to avoid HRI. Still, given the growing threat and Florida’s high numbers of HRI, a fully enforceable standard, regulation, or law is needed.

Besides limiting the preemption of local approaches, the Florida Legislature should pass legislation like the Zachary Martin Act that extends protections to all working people. Such a law would require staff training, heat-illness prevention protocols, and enforcement capacity to support its mandates. While it lacks strict enforcement language, advocates have gotten the Legislature to file — yet not pass — a bill requiring outdoor employers to mitigate heat illness nearly every year since 2018.[60]

Finally, Florida should consider joining the 29 states that have a state-approved OSHA plan, including its Southern neighbors Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and the Carolinas. A state-approved plan would ensure that Florida's public workers are covered when OSHA develops a heat-related illness standard. Without such a plan, OSHA only protects Floridians working in the private sector (i.e., for corporations and nonprofits).[61]

Methodology

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) May 2024 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates (OEWS), the number employed in outdoor roles totals 611,100 Floridians. Per the BLS, "The OEWS survey covers wage and salary workers in non-farm establishments and does not include the self-employed, owners and partners in unincorporated firms, household workers, or unpaid family workers."

To determine this total number of outdoor working Floridians, FPI built on the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ 2017 list of outdoor careers. To round out this list, FPI added roles (and their corresponding North American Industry Classification codes) that require working outside more than half of the time.[62] While this list is not comprehensive, it represents the occupations most likely to work outdoors for a large share of time. Not all workers in these categories are outdoors consistently:

1. Agricultural Equipment Operators (NAICS 45-2091)

2. Agricultural Inspectors (45-2011)

3. Agricultural Workers, All Other (45-2099)

4. Amusement and Recreation Attendants (39-3091)

5. Animal Caretakers (39-2021)

6. Athletes and Sports Competitors (27-2021)

7. Brickmasons and Blockmasons (47-2021)

8. Captains, Mates, and Pilots of Water Vessels (53-5021)

9. Cement Masons and Concrete Finishers (47-2051)

10. Civil Engineers (17-2051)

11. Coaches and Scouts (27-2022)

12. Commercial Divers (49-9092)

13. Conservation Scientists (19-1031)

14. Construction Laborers (47-2061)

15. Construction Managers (11-9021)

16. Crane and Tower Operators (53-7021)

17. Crossing Guards and Flaggers (33-9091)

18. Derrick Operators, Oil and Gas (47-5011)

19. Dredge Operators (53-7031)

20. Earth Drillers, Except Oil and Gas (47-5023)

21. Electrical Power-Line Installers and Repairers (49-9051)

22. Entertainers and Performers, Sports and Related Workers, All Other (27-2099)

23. Farmers, Ranchers, and Other Agricultural Managers (11-9013)

24. Farmworkers and Laborers, Crop, Nursery, and Greenhouse (45-2092)

25. Farmworkers, Farm, Ranch, and Aquacultural Animals (45-2093)

26. Fence Erectors (47-4031)

27. First-Line Supervisors of Construction Trades and Extraction Workers (47-1011)

28. Fish and Game Wardens (33-3031)

29. Forest and Conservation Technicians (19-4071)

30. Forest and Conservation Workers (45-4011)

31. Forest Fire Inspectors and Prevention Specialists (33-2022)

32. Foresters (19-1032)

33. Helpers--Brickmasons, Blockmasons, Stonemasons, and Tile and Marble Setters (47-3011)

34. Helpers—Roofers (47-3016)

35. Highway Maintenance Workers (47-4051)

36. Hoist and Winch Operators (53-7041)

37. Landscaping and Groundskeeping Workers (37-3011)

38. Lifeguards, Ski Patrol, and Other Recreational Protective Service Workers (33-9092)

39. Log Graders and Scalers (45-4023)

40. Logging Equipment Operators (45-4022)

41. Logging Workers, All Other (45-4029)

42. Manufactured Building and Mobile Home Installers (49-9095)

43. Meter Readers, Utilities (43-5041)

44. Motorboat Operators (53-5022)

45. Operating Engineers and Other Construction Equipment Operators (47-2073)

46. Painters, Construction and Maintenance (47-2141)

47. Parking Enforcement Workers (33-3041)

48. Paving, Surfacing, and Tamping Equipment Operators (47-2071)

49. Pile Driver Operators (47-2072)

50. Pipelayers (47-2151)

51. Plasterers and Stucco Masons (47-2161)

52. Postal Service Mail Carriers (43-5052)

53. Railroad Brake, Signal, and Switch Operators and Locomotive Firers (53-4022)

54. Rail-Track Laying and Maintenance Equipment Operators (47-4061)

55. Recreation Workers (39-9032)

56. Refuse and Recyclable Material Collectors (53-7081)

57. Riggers (49-9096)

58. Roofers (47-2181)

59. Rotary Drill Operators, Oil and Gas (47-5012)

60. Roustabouts, Oil and Gas (47-5071)

61. Sailors and Marine Oilers (53-5011)

62. Self-Enrichment Teachers (25-3021)

63. Septic Tank Servicers and Sewer Pipe Cleaners (47-4071)

64. Service Unit Operators, Oil and Gas (47-5013)

65. Ship Engineers (53-5031)

66. Signal and Track Switch Repairers (49-9097)

67. Solar Photovoltaic Installers (47-2231)

68. Structural Iron and Steel Workers (47-2221)

69. Surveyors (17-1022)

70. Tank Car, Truck, and Ship Loaders (53-7121)

71. Telecommunications Line Installers and Repairers (49-9052)

72. Tour and Travel Guides (39-7010)

73. Tree Trimmers and Pruners (37-3013)

74. Umpires, Referees, and Other Sports Officials (27-2023)

75. Zoologists and Wildlife Biologists (19-1023)

In Figure 2, FPI narrowed this list of outdoor occupations to those with 5,000 or more employees and then analyzed the same OEWS data. Electrical Power-Line Installers and Repairers (49-9051) and Telecommunications Line Installers and Repairers (49-9052) were combined to display “Line Installers and Repairers.” The following three categories were combined to display “Farmworkers”: Farmworkers and Laborers, Crop, Nursery, and Greenhouse (45-2092); Farmworkers, Farm, Ranch, and Aquacultural Animals (45-2093); and Agricultural Workers, All Other (45-2099).

Notes

[1] FPI analysis of May 2024 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates data for Florida: https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_fl.htm. See Methodology for full list of occupations included in this estimate.

[2] Elka Torpey, “Jobs for People Who Love Being Outdoors,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, July 2017, https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2017/article/outdoor-careers.htm.

[3] Rebecca L. Reindel and Ayusha Shrestha, “Death on the Job: The Toll of Neglect (33rd edition),” AFL-CIO—Safety and Health Department, April 2024, https://aflcio.org/reports/dotj-2024.

[4] U.S. Department of Labor-Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), “Heat: Heat-Related Illnesses and First Aid,” https://www.osha.gov/heat-exposure/heat-illness#:~:text=Heat%20exhaustion%20is%20the%20body’s,in%20muscles%20cause%20painful%20cramps.

[5] Alan Buis, “A Degree of Concern: Why Global Temperatures Matter - NASA Science,” National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), June 19, 2019, https://science.nasa.gov/earth/climate-change/vital-signs/a-degree-of-concern-why-global-temperatures-matter/.

[6] InfluenceMap, “The Carbon Majors Database: Launch Report,” April 2024, https://carbonmajors.org/briefing/The-Carbon-Majors-Database-26913.

[7] National Aeronautics and Space Administration, “NASA Data Shows July 22 Was Earth’s Hottest Day on Record,” July 29, 2024, https://www.nasa.gov/earth/nasa-data-shows-july-22-was-earths-hottest-day-on-record/.

[8] Emily Powell, “2024 Annual Florida Weather & Climate Summary,” Florida Climate Center: Office of the State Climatologist, February 2025, https://climatecenter.fsu.edu/images/docs/Fla_Annual_climate_summary_2024.pdf.

[9] Emily Powell, February 2025.

[10] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), ”What Climate Change Means for Florida,“ August 2016, https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-08/documents/climate-change-fl.pdf.

[11] U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)-National Weather Service (NWS), “What Is the Heat Index,” https://www.weather.gov/ama/heatindex.

[12] FPI analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), May 2024 Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) Survey, Florida, www.bls.gov/oes/tables.htm. See Methodology for full list of occupations included in this estimate.

[13] Mitchel Harmon, “Heat Stress in the Workplace: A Study of Extreme Heat And How It Impacts Workers in Central Florida,” Central Florida Jobs with Justice, 2023, https://www.cfjwj.org/heatresearch.

[14] Reindel and Shrestha.

[15]Jisung Park, Nora M. C. Pankratz, and A. Behrer, “Temperature, Workplace Safety, and Labor Market Inequality,” IZA Discussion Paper No. 14560, 2021, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3892588.

[16] Juley Fulcher, “The Cost of Inaction,” Public Citizen, October 4, 2022, https://www.citizen.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Cost-of-Inaction-report-Oct-2022.pdf.

[17] Fulcher.

[18] Atlantic Council-Adrienne Arsht Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center and Vivid Economics, “Extreme Heat: The Economic and Social Consequences for the United States,” August 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Extreme-Heat-Report-2021.pdf.

[19] Park, Pankratz, and Behrer.

[20] Reindel and Shrestha.

[21] OSHA, “Heat Illness Prevention Campaign - Employer Responsibilities,” https://www.osha.gov/heat/employer-responsibility.

[22] OSHA, “Heat Injury and Illness Prevention in Outdoor and Indoor Work Settings Rulemaking,” https://www.osha.gov/heat-exposure/rulemaking. On July 1, 2024, OSHA announced its “unofficial version of the Heat Injury and Illness Prevention in Outdoor and Indoor Work Settings proposed rule.” FPI testified at the public hearing in July 2025. OSHA is still allowing public comments until September 30, 2025. This is stage 3 of a 5-step process to finalize the rule language, so it could still be many months before a federal standard is in place.

[23] OSHA, “Prevention-Heat Hazard Recognition,” https://www.osha.gov/heat-exposure/hazards.

[24] OSHA, “US Department of Labor Cites Wauchula Labor Contractor after 35-Year-Old Farmworker Suffers Fatal Heat Illness,” August 24, 2022, https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/osha/osha20220824-1.

[25] OSHA, “US Department of Labor Cites Okeechobee Labor Contractor after Heat Illness Claims the Life of 28-Year-Old Farmworker in Parkland,” June 28, 2023, https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/osha/osha20230628-0.

[26] Mei Ching Lim et al., ” Risk Factors and Heat Reduction Intervention Among Outdoor Workers: A Narrative Review,” Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences, Vol. 19, December 2023,

https://medic.upm.edu.my/upload/dokumen/2024020210581524_2022-1259.pdf.

[27] Larry L. Jackson and Howard R. Rosenberg, ”Preventing Heat-Related Illness Among Agricultural Workers,” Journal of Agromedicine, Vol. 15, 2010, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20665306/.

[28] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), ”Acclimatization,” August 14, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/heat-stress/recommendations/acclimatization.html.

[29] National Labor Relations Board, ”Frequently Asked Questions – NLRB, Which Employees are Protected Under the NLRA,” n.d., https://www.nlrb.gov/resources/faq/nlrb.

[30] See Methodology for the 24 Construction and Extraction Occupations (North American Industry Classification System occupation category 47) FPI included in its analysis of May 2024 OEWS data to arrive at this estimate. Construction Managers were included in this report’s overall estimates of outdoor workers. However, they were excluded from the Construction industry estimate of 262,530 outdoor workers because the BLS classifies Construction Managers as Management Occupations (NAICS 11-000).

[31] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Industries at a Glance: Construction: NAICS 23,” https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag23.htm . Note that the larger Sector 23-Construction includes the NAICS occupation codes for Construction and Extraction Occupations (47-000) used in this report.

[32] Park, Pankratz, and Behrer.

[33] National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA)-Construction Sector Council, “National Occupational Research Agenda for Construction,“ June 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docket/review/docket298/pdfs/298-updated-national_occupational_research_agenda_for_construction_june_2018_508_v2.pdf.

[34]FPI analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s Annual Business Survey data for 2022 (latest year available) shows there are 44,548 construction firms (NAICS code – 23) in Florida with sales/receipts under $1,000,000 out of 62,231 total Florida construction firms. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2022/econ/abs/2022-abs-company-summary.html.

[35] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, “Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2023, 37-3011 Landscaping and Groundskeeping Workers,” updated April 3, 2024, https://www.bls.gov/oes/2023/may/oes373011.htm.

[36] U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “News Release” February 28, 2019, https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/osha/osha20190228.

[37] U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, ”OSHA Instruction: National Emphasis Program – Outdoor and Indoor Heat-Related Hazards,” April 8, 2022, https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/enforcement/directives/CPL_03-00-024.pdf.

[38] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, ”Occupational Outlook Handbook: Agricultural Workers,” updated April 18, 2025 https://www.bls.gov/ooh/farming-fishing-and-forestry/agricultural-workers.htm#tab-2.

[39] Reindel and Shrestha.

[40] Public Citizen and Farmworker Association of Florida, “Unworkable: Dangerous Heat Puts Florida Workers at Risk,” October 2018, https://www.citizen.org/wp-content/uploads/public-citizen-et-al-unworkable-fl-heat-stress-october-2018-1.pdf.

[41] WeCount!, “Comments in Support of the Proposed Safety Standard for Heat Injury and Illness Prevention in Outdoor and Indoor Work Settings and Recommendations for Strengthening the Rule,” January 14, 2025, provided to FPI via email June 2025.

[42] Linda Gordon, Pitied But Not Entitled: Single Mothers and the History of Welfare, 1890-1935, Cornell University Press, 1994, p. 5.

[43] The National Agricultural Law Center, “Labor--An Overview,” https://nationalaglawcenter.org/overview/labor/.

[44] U.S. Department of Labor, OSHA News Release – Atlanta Region, “U.S. Department of Labor Cites South Florida Contractor for Lack of Heat Illness Prevention Program After Heatstroke Claims 26-Year-Old Worker’s Life,” April 15, 2024, https://www.osha.gov/news/newsreleases/region4/04152024.

[45] Jackson and Rosenberg.

[46] Florida Department of Health, ”Migrant Farmworker Housing,” updated April 3, 2024, https://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/migrant-farmworker-housing/index.html#:~:text=150%2C000%20to%20200%2C000%20migrant%20and,exceeds%20standards%20set%20by%20law.

[47] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS), “Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2023: 39-3091 Amusement and Recreation Attendants,” https://www.bls.gov/oes/2023/may/oes393091.htm.

[48] Walt Disney World, Disney in Florida, ”Company Highlights,” https://disneyexperiences.com/disneyworld/.

[49] Unite Here Local 737, ”Contracts: Disney, 2022-2027 Full Time STCU Contract,” https://www.uniteherelocal737.org/wp-content/uploads/2022-2027-Full-Time-STCU-Contract-with-MOUs-and-Letters.pdf; United Here Local 737, ”Contracts: Disney, 2022-2027 Part Time STCU Contract,” https://www.uniteherelocal737.org/wp-content/uploads/2022-2027-WDW-STCU-PT-Final-Bolded-Contract-With-Side-Letters-and-MOUs.pdf.

[50] McKenna Schueler, “As Florida Temperatures Soar, Disney World Workers Struggle and Pass Out From the Heat,” Orlando Weekly, July 17, 2024, https://www.orlandoweekly.com/news/as-florida-temperatures-soar-disney-world-workers-struggle-and-pass-out-from-the-heat-37296618.

[51] McKenna Schueler, ”Florida Lobbyists Leaned on Pols to Get Ban On Local Heat Safety and Wage Laws Across the Finish Line, Records Show,” Orlando Weekly, April 19, 2024, https://www.orlandoweekly.com/news/florida-lobbyists-leaned-on-politicians-to-get-ban-on-local-heat-safety-and-wage-laws-across-the-finish-line-records-show-36667788.

[52] Jason Garcia, ”No Water, No Shade: How Homebuilders, Farming Companies And Construction Firms Got Politicians To Reject Heat Rules For Outdoor Workers In Florida,” Seeking Rents, May 26, 2024, https://jasongarcia.substack.com/p/no-water-no-shade-how-homebuilders.

[53] The Florida Senate, “CS/HB 7011 -- Student Athletes,” 2020, https://www.flsenate.gov/Committees/billsummaries/2020/html/2173.

[54] U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, ”Heat, Prevention – Water, Rest, Shade.”

[55] From Public Citizen and The Farmworker Association of Florida: “In the mornings, we would start work in the fields where it is very hot, because in the mornings, you don’t feel it so much, right? But between noon and 2pm in the afternoon, there is a very intense heat. What they should do in the afternoons is move us to an area where there is a little bit of a breeze or air circulation or a little bit of shade during the time when it is hottest. And they should give us water or ice. This is what we would like, what the employers ought to give us, that they give us a little bit of consideration on this.”

[56] CDC-NIOSH, “Heat Stress - Recommendations.”

[57] A key campaign in Florida to address heat-related illness, Que Calor, is by WeCount!, an immigrant-led nonprofit organization. WeCount!, “Que Calor,” https://www.we-count.org/quecalor.

[58] Alexis Tsoukalas and Adriana Sela, “The Florida Timeline—Worker Justice,” Florida Policy Institute, October 2023 https://www.floridatimeline.org/worker-justice/.

[59] Laws of Florida, Chapter 2024-80, https://laws.flrules.org/2024/80.

[60] Senate Bill 510 and House Bill 35 (2025); Senate Bill 762 and House Bill 945 (2024); Senate Bill 706 and House Bill 903 (2023); Senate Bill 732 and House Bill 887 (2022); Senate Bill 882 and House Bill 513 (2020); Senate Bill 1538 and House Bill 1285 (2019); Senate Bill 1766 (2018).

[61] OSHA, “State Plan Frequently Asked Questions,” https://www.osha.gov/stateplans/faqs.

[62] Based on occupation survey responses to the Occupational Information Network (O*NET), https://www.onetonline.org/find/all.